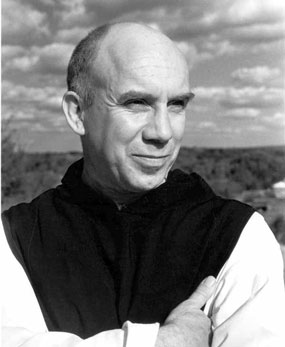

Forty-five years ago today, on 10 December 1968, Thomas Merton – perhaps the twentieth century’s most famous monk – died. Exactly 27 years earlier, on 10 December 1941, he had joined the Gethsemane Abbey in the United States.

Merton lends himself to comparison with Augustine. He exploited his youth with intensity, espousing atheism and nihilism, drinking excessively and womanising enthusiastically. Like Augustine, he fathered a child prior to his conversion. Even after his conversion, he struggled against his passions; he confessed to “continual, uninterrupted resentment” towards monastic life — something he did not consent to, but which manifested itself anyway. At one point, he fell deeply in love with a nurse half his age, and though he confessed his love to her and exchanged love letters, he did not break his vows, and ultimately broke off the relationship.

I have not read any of his works, but after today I’m resolved to read his first and most famous book, The Seven Storey Mountain. The book is a spiritual autobiography, which documents his conversion. Merton’s genius, it is said, is his ability to describe God’s love in terms which resonate with our peculiarly modern aspirations and foibles.

Principally what makes the Mountain worth reading is that as he looks into his past Merton loves himself and forgives himself, and loves and forgives everyone else too. This doesn’t mean that he thinks that what he did was good, just that he looks on it dispassionately and sees its proper place in his life. He has drunk of Dante’s Lethe and Eunoë, and so remembers his sins “only as an historical fact and as the occasion of grace and blessedness.” (From Universalis.)

That’s a great recommendation. In the confessional, I often advise penitents not to be discouraged when they fall, but in the spirit of St Paul, to see their sinfulness as an opportunity to receive grace and foster humility:

To keep me from being too elated by the abundance of revelations, a thorn was given me in the flesh, a messenger of Satan, to harass me, to keep me from being too elated. Three times I besought the Lord about this, that it should leave me; but he said to me, “My grace is enough for you; for my power is made perfect in weakness.” I will all the more gladly boast of my weaknesses, that the power of Christ may rest upon me. (2 Cor 12:9ff)

Of course, in relating this advice to others, I’d do well to heed the words myself. So, in the hope that Merton’s reflections might help me in this, I have duly added The Seven Storey Mountain to my summer reading. Here’s a foretaste:

Therefore, another one of those times that turned out to be historical, as far as my own soul is concerned, was when Lax and I were walking down Sixth Avenue, one night in the spring. The Street was all torn up and trenched and banked high with dirt and marked out with red lanterns where they were digging the subway, and we picked our way along the fronts of the dark little stores, going downtown to Greenwich Village. I forget what we were arguing about, but in the end Lax suddenly turned around and asked me the question: “What do you want to be, anyway?”

I could not say, “I want to be Thomas Merton the well-known writer of all those book reviews in the back pages of the Times Book Review,” or “Thomas Merton the assistant instructor of Freshman English at the New Life Social Institute for Progress and Culture,” so I put the thing on the spiritual plane, where I knew it belonged and said: “I don’t know; I guess what I want is to be a good Catholic.”

“What do you mean, you want to be a good Catholic?”

The explanation I gave was lame enough, and expressed my confusion, and betrayed how little I had really thought about it at all. Lax did not accept it.

“What you should say” — he told me — ”what you should say, is that you want to be a saint.”

A saint! The thought struck me as a little weird. I said: “How do you expect me to become a saint?”

“By wanting to,” said Lax, simply.

“I can’t be a saint,” I said, “I can’t be a saint.” And my mind darkened with a confusion of realities and unrealities: the knowledge of my own sins, and the false humility which makes men say that they cannot do the things that they must do, cannot reach the level that they must reach: the cowardice that says: “I am satisfied to save my soul, to keep out of mortal sin,” but which means, by those words: “I do not want to give up my sins and my attachments.”

The entire book is available online, though I recommend you find yourself a hard copy too!

A hard copy can be obtained from bookdepository.com for approx $15 post free.

“O happy fault that earned so great, so glorious a Redeemer”

– from the Exsultet, Easter Vigil

I read Seven Storey Mountain thirty-three years ago and for me it was, as you point out from various commentaries, the humbling testimony of someone who has discovered the pearl of great value, the treasure buried in the field.

The Easter Vigil for me and that particular line in the Exsultet has always unlocked a deeper sense of what life really is about and it comes as we look back, with Christ’s Redemption, to the past from which we are and always will be, liberated from, by the Cross and the Resurrection.

Sadly, the Easter Vigil is becoming not the great celebratory liturgy it needs to be, but something most Catholics avoid because they say it’s too long.

Father, shamefully I admit I haven’t heard of Thomas Merton before. Thank you for the recommendation and bringing to your readers new ideas. God bless.

Well on December the 9TH in 1848 the first Jesuits priests Australia at Port Adelaide. They came on ship called the Alfred with about 275 passagers on board! The two priests were Fr. Krnwitter and Fr. Klinkowstrom! Fr. John you would know more information when you went to the vineyard few years ahttp://www.abc.net.au/landline/content/2010/s2919483.htmgo now!