There is a wonderful insight from St Vincent de Paul, in the Office of Readings on his feast day. It’s an insight that probably every saint has received and shared — not to mention countless disciples who aren’t canonised. But St Vincent has most famously formulated it:

Do not become upset or feel guilty because you interrupted your prayer to serve the poor. God is not neglected if you leave him for such service. One of God’s works is merely interrupted so that another can be carried out. So when you leave prayer to serve some poor person, remember that this very service is performed for God.

Godly “distractions” aren’t limited to serving the poor. For example, when you’re trying to meditate, focusing your thoughts on God, but other thoughts invade — that conversation you had yesterday, or that friend you haven’t called for a while — that may not be a “distraction.” That may be an indication, from God, to pray for that person, for his or her intentions; or to get in touch.

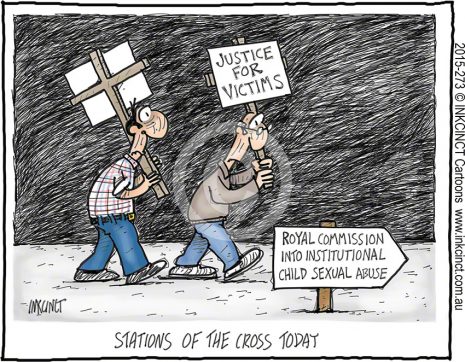

In the same way, although it is understandable to consider the clergy abuse scandal as a devastating distraction from the Church’s mission, maybe even a diabolical means of destroying the Church’s moral authority, I suspect the opposite. The never-ending Royal Commission, the hostile media coverage, the horrendous stories and shameful statistics — maybe none of this is a distraction. Maybe this is where God wants the Church to focus its attention. Maybe this is central to the mission of the Church in Australia.

It’s becoming more and more evident, I think, that the sexual abuse of children is not ‘a Catholic problem,’ and nor is it an historical problem. Studies suggest a substantial proportion of Australian children are abused, and that the rate of abuse is growing. This is a universal problem, and a current one. The world is in trouble. And the Church exists for the world, not for itself.

The Catholic Church has sustained a humiliating exposé which has done a lot of harm. But it’s not in vain. In fact, I think the benefits of this shameful exposé outweigh the costs. Catholic schools and parishes are now the safest places for children in Australia, and Catholic schools and parishes are the most dangerous places for paedophiles. The staff in my parish schools, and all the people on my parish councils, and I, have signed and abide by codes of conduct which eliminate opportunities for adults to prey on children. We all know what to do if we believe someone violates the code — how to respond, who to speak to, which legal authorities to call. That’s significant. Paedophiles cultivate and groom adults, not just children. They depend on the naiveté and inaction of good people. A culture which eliminates that possibility saves children.

That’s the future, but the present is maybe even more important. A lot of pastoral care is owed to a lot of people who have suffered from clerical child abuse. And a lot can be learned from them too. Their suffering is not in vain either; their experiences and their insights can enrich the Church and assist its mission. These victims and survivors are not apart from the Church. They are the Church. Christ identifies with them, and so should we all. I hope Church leaders are listening to them. We have so much more to learn.

To paraphrase St Vincent:

Do not become upset or feel guilty because the evangelising mission of the Church is interrupted by the fallout and response to the clergy abuse scandal. God is not neglected if you leave him for such service. One of God’s works is merely interrupted so that another can be carried out. Remember that this very service is performed for God.

None of this is a distraction. This is where we need to focus our energy. Our prayer. Our apostolic zeal. God knows what he is about.

Recent Comments