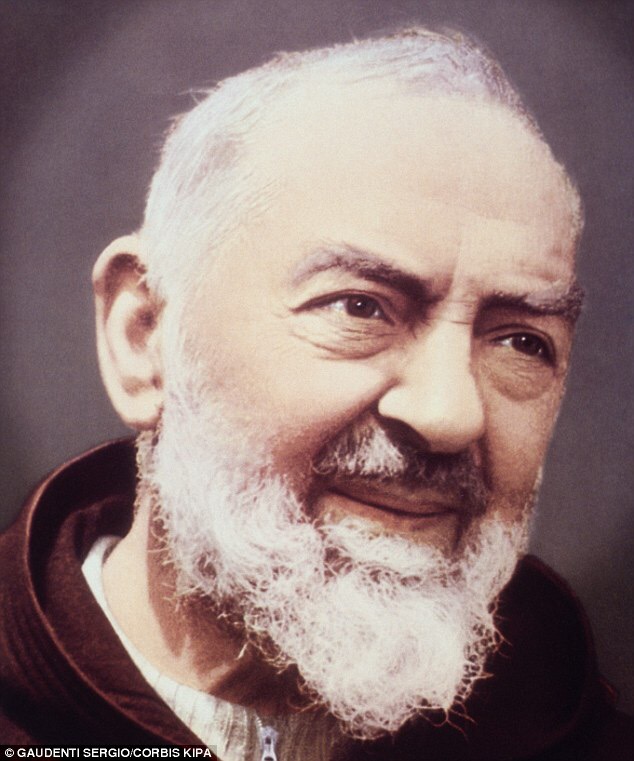

The feast of Padre Pio is a good occasion to repeat my invitation to a priests’ pilgrimage which honours and seeks the intercession of St Pio and several other great saints of the confessional.

If you know a priest who might be interested in celebrating the Jubilee of Mercy with Pope Francis, and becoming a holier minister of divine mercy, please direct them to www.jmpriests.com.

I must confess I don’t have much devotion to St Pio, although I’m familiar with him obviously. I watched a movie on his life when I was in the seminary. I’m fairly sure it’s this one, which you can view for free on YouTube:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VOdHZiuKq68

But I’m afraid the movie just confirmed my prejudice that Padre Pio was a grouchy eccentric, whose company I would avoid. I’m sure this characterisation is unfair, and friends have recommended books about him which will revise my thinking.

Maybe my prejudice derives from the knowledge that St Pio sometimes deferred or even refused absolution. That was a common practice in centuries past, but it’s almost unthinkable now. St Josemaría, for example, advised against it, because in the modern context it can drive penitents away from the sacrament and the Church. Padre Pio, though, was in a unique position: like the Curé of Ars a century earlier, crowds made the pilgrimage specifically to his confessional. In that context, I doubt he ever drove anyone away.

In any event, sometimes the priest has no choice but to refuse absolution, though it is never done lightly. Graham Greene always excelled at evoking the dramatic tension present in the Catholic moral vision. Here’s his take on what the refusal of absoltion looks like, from The Heart of the Matter:

Kneeling in the space of an upturned coffin he said, ‘Since my last confession I have committed adultery.’

‘How many times?’

‘I don’t know, Father, many times.’

‘Are you married?’

‘Yes.’ He remembered that evening when Father Rank had nearly broken down before him, admitting his failure to help … Was he, even while he was struggling to retain the complete anonymity of the confessional, remembering it too? He wanted to say, ‘Help me, Father. Convince me that I would do right to abandon her to Bagster. Make me believe in the mercy of God,’ but he knelt silently waiting: he was unaware of the slightest tremor of hope.

Father Rank said, ‘Is it one woman?’

‘Yes.’

‘You must avoid seeing her. Is that possible?’

He shook his head.

‘If you must see her, you must never be alone with her. Do you promise to do that, promise God not me?’

He thought: how foolish it was of me to expect the magic word. This is the formula used so many times on so many people. Presumably people promised and went away and came back and confessed again. Did they really believe they were going to try? He thought: I am cheating human beings every day I live, I am not going to try to cheat myself or God. He replied, ‘It would be no good my promising that, Father.’

‘You must promise. You can’t desire the end without desiring the means.’

Ah, but one can, he thought, one can: one can desire the peace of victory without desiring the ravaged towns.

Father Rank said, ‘I don’t need to tell you surely that there’s nothing automatic in the confessional or in absolution. It depends on your state of mind whether you are forgiven. It’s no good coming and kneeling here unprepared. Before you come here you must know the wrong you’ve done.’

‘I do know that’

‘And you must have a real purpose of amendment. We are told to forgive our brother seventy times seven and we needn’t fear God will be any less forgiving than we are, but nobody can begin to forgive the uncontrite. It’s better to sin seventy times and repent each time than sin once and never repent.’

He could see Father Rank’s hand go up to wipe the sweat out of his eyes: it was like a gesture of weariness. He thought: what is the good of keeping him in this discomfort? He’s right, of course, he’s right. I was a fool to imagine that somehow in this airless box I would find a conviction … He said, ‘I think I was wrong to come, Father.’

‘I don’t want to refuse you absolution, but I think if you would just go away and turn things over in your mind, you’d come back in a better frame of mind.’

‘Yes, Father.’

‘I will pray for you.’

When he came out of the box it seemed to Scobie that for the first time his footsteps had taken him out of sight of hope. There was no hope anywhere he turned his eyes: the dead figure of the God upon the cross, the plaster Virgin, the hideous stations representing a series of events that had happened a long time ago. It seemed to him that he had only left for his exploration the territory of despair.

I think this is an extremely unlikely scenario these days. In our culture, nobody would bother going to confession if they weren’t already contrite.

Evelyn Waugh’s take, from Brideshead Revisited, is a more likely scenario. Julia has just learned that her fiancé is sleeping with another woman. Rex, whom we’re never supposed to like, blames Julia’s chastity. ‘What do you expect?’ he said. ‘What right have you to ask so much, when you give so little?’

She took her problem to Farm Street and propounded it in general terms, not in the confessional, but in a dark little parlour kept for such interviews.

‘Surely, Father, it can’t be wrong to commit a small sin myself in order to keep him from a much worse one?’

But the gentle old Jesuit was unyielding. She barely listened to him; he was refusing her what she wanted, that was all she needed to know.

When he had finished he said, ‘Now you had better make your confession.’

‘No, thank you,’ she said, as though refusing the offer of something in a shop. ‘I don’t think I want to today,’ and walked angrily home.

From that moment she shut her mind against her religion.

I like both these scenes very much. They’re a good reminder that no one is compelled in the sacrament of confession. Freedom is paramount, and so is conscience, and so is Truth. Three absolutes which should be in harmony, but in the mess of the human condition, they are in tension.

Here’s my view: problems of this kind are inevitable if the sacrament is viewed as an instrument of justice, where the priest has some kind of quasi-judicial role, some discretion. Let me clarify.

The act of confessing a sin, or what one imagines is a sin, is an act of will. It is an act, in other words, of intent. The act is a humbling act, from start to finish: it cannot be made without – in most usual cases – some predisposition to submit, or of recognition, of some self-awareness, of sinfulness, and some impulse to reconcile or be reconciled. No human can ever guarantee commitment, but for someone to approach the confessional in the first place is as sound an evidence of repentance – of some kind – as you ever may reasonably expect. To refuse absolution, which is Christ’s mercy, not the priest’s, seems to me to be quite beyond a priest’s capacity.

I think there is much misdirection, misconception, in any attitude or rule that would make this quintessential application of Christ’s mercy conditional. This whole Sacrament is established on the foundations of human frailty and imperfection. Indeed it derives its meaning and relevance on this, including the limitations and any hesitations of the will that presents itself. It is certainly not established on supposedly angelic constitutions.

If I were forced to choose between Padre Pio who would refuse absolutions, and Don Escrivar who would not, then there is no contest.

Well it’s nearly the weekend! So it is time for more racing tips! I do Caulfield and maybe later or tomorrow I do Coleraine Cup Day on Sunday! Maybe Fr. Corrigan might add some comments about that!

Well at Caulfield I like Race2No5 Gloryland

Race3No3,7, and 12

Race4No 4 and 9

Race5No6 Reemah

Race6No4. Metallic Crown

Race7No12. Hi World

Race8No5and 11

Race9No10 and 14.

Over in at Morpettivvle I like Race8no12

Happy Weeekend and and Happy Punting from Simon the Pieman.

Graham Greene was a sophisticated sentimentalist and he tried to twist sin into something imponderable, complicated, inevitable and just about unredeemable.

Greene had the nerve to use Fr Cassaude’s theology of Self-Abandonment to Divine Providence as a fatalistic excuse to justify his adultery.

It’s not that hard. Catholic priests certainly can withhold absolution and for clear and unequivocal reasons: if the penitent is not penitent and has no intention of abandoning the sin.

This is quite distinct from having no trust in one’s own strength, a pessimism about being able to refrain from the sin, but hoping for God’s grace and resolving to do something about the situation.

Isn’t it?