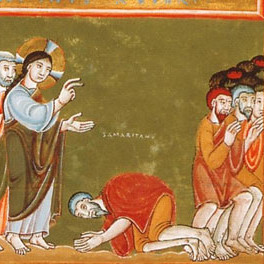

It’s instructive, I think, how much Jesus objects to the self-righteous hypocrisy of the Pharisees. In today’s Gospel he enumerates many sins, but nothing raises his ire like the Pharisaical spirit.

When thieves, murderers, adulterers, cross the Lord’s path, they encounter his mercy. They are moved to contrition. But the moral superiority of the Pharisees elicits a very different response from Jesus, probably because it is impervious to mercy. I’m reminded of C. S. Lewis’ insightful warning:

“Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.”

Put that way, it’s easy to discern that the Pharisaical spirit is not exclusively religious. There are plenty of moralistic tyrants populating the secular sphere. A few contributors to the global warming and marriage equality debates come to mind.

Nonetheless, the Pharisaical spirit is especially odorous in the religious sphere. It caused the Pharisees to believe they were better than God. Literally. That sort of moral superiority is anathema to Christian discipleship.

Our Lord wants all his disciples, I think, to sincerely believe, and frequently recall, “I am a sinner.” But on its own, that’s not enough. The world abounds with sinners who proudly declare, “I am a sinner,” and extol their wickedness as a badge of honour. How many sins are used as attractive marketing techniques? How many vices have been redefined as virtue?

It’s true that this sort of shamelessness is a safeguard against the Pharisaical spirit, but like Pharisaism, it’s impervious to divine mercy, which means that it’s just as toxic. And yet the opposite of shamelessness — shame — is no less disastrous. Shamelessness and shame are both forms of pride. They are both egotistical. Shame is centered on the self: “I’m so ashamed of myself.” “What will people think of me?”

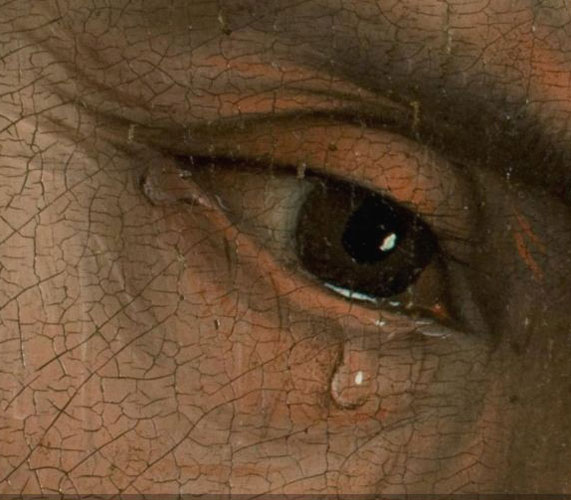

Shame prevents a person from publicly admitting guilt. Shame causes us to avoid the people we’ve offended. We delay seeking forgiveness. Shame discourages us, and we can wander far from God. Shame usually comes from our own ego, it can come from the evil one, but it never comes from the Holy Spirit. It’s never good to dialogue with shame.

Guilt, on the other hand, does come from the Holy Spirit. Where shame is focused on ourselves, guilt is focused on the wrong we’ve done. When we do something wrong, when we use our freedom selfishly, when we ignore or injure or demean God or ourselves or our neighbour, our conscience bothers us; we feel guilty. Thanks be to God! Guilt is a means to conversion; an impulse to seek forgiveness and make amends.

Guilt is good thing, which safeguards us from the proud spirits of Pharisaism, shamelessness, and shame. But more importantly, guilt makes us responsive to mercy, and grateful for it. A person with a healthy sense of guilt actively seeks divine mercy, and generously ministers mercy to others.

Put guilt and mercy together, I think, and you have a great recipe for humility and love. “I am a sinner,” the Lord wants us to say. But more than that: “I am a sinner, madly in love with God.”

You’re forgetting Australia is nearly half a day ahead of you Lourdesman. I’ve already offered three Sunday Masses today. Pax.

Thanks very much for this article, Fr John, and also for your always solemn, devout and reverent celebration of the Mass.

Not to mention your patience in the teeth of such vicious attacks from the type of self-appointed moral arbiter mentioned in your article.

God bless you!

Nice article, thanks Fr. John. With all the talk of an empty hell, it’s good to be reminded that heaven isn’t empty either, as some Ubercaths would have us believe.

You say potato, I say potato, Lourdesman.