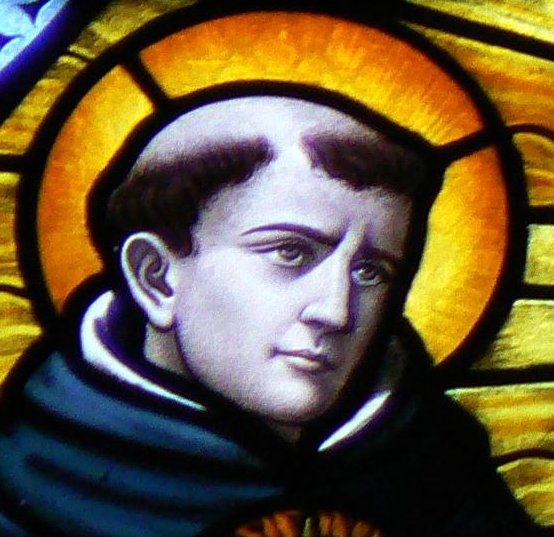

Today is the feast of “the Angelic Doctor,” St Thomas Aquinas. Studying at the Abbey of Monte Cassino as a boy, Thomas interrogated every new teacher with the same question: “Who is God? Please explain God to me.”

Eventually, of course, Thomas concluded that knowing God is not a question of mere study, but above all else a spiritual endeavour. Shortly before his death, on the feast of St Nicholas, 6 December 1273, the saintly priest stopped writing. A brother Dominican, Reginald of Piperno, recalls the day:

He was excited by an extraordinary alteration, and after that Mass never wrote or dictated anything; indeed, he hung up his instruments of writing in the third part of the Summa [Thomas’ masterpiece], in the treatise on penance.

Something had happened, but what? Eventually, Reginald secured this admission from Thomas (revealed posthumously):

“I adjure you by the living almighty God, and by the faith you have in our order, and by charity that you strictly promise me you will never reveal in my lifetime what I tell you. Everything that I have written seems like straw to me compared to those things that I have seen and have been revealed to me.”

We shouldn’t take that as a repudiation of Thomas’ work, much less a repudiation of study. Thomas bequeathed us a monumental synthesis of faith and reason. The truth and beauty and goodness of God is ultimately beyond our comprehension, but St Thomas nonetheless teaches us to seek the Lord with intelligence, study, love and prayer.

St Thomas embodies two ideals we can all aspire to: the piety of children and the doctrine of theologians. The study of doctrine doesn’t self-evidently recommend itself. It is often associated with dry intellectualism, or worse, dogmatism: all-knowing; over-bearing; close-minded.

Nonetheless, a balanced Christian life demands a sound knowledge of doctrine, and an ability to expound it. So much so, that the study of doctrine is a serious obligation of every Christian. St Teresa of Avila was known for insisting on this. “The person who knows God is better able to do His works,” she said.

- Study serves the apostolate. We need to have answers to attract others to Christ. Not by way of over-bearing argument, but by presenting the Faith ― when a situation demands it ― with clarity and precision. The best apologists are measured not by knowledge and intelligence, but by wisdom, humility and sincerity. Some of the best apologists I have met are grade three children preparing for the sacraments. They will often startle me with a profound insight I had not considered. Why? Because they are studying their faith in faith, which becomes a dialogue with God.

- Study also nourishes our love of God. We cannot love what – or who – we do not know. In order to more deeply know Jesus, many Christians dedicate some minutes each day to reading and meditating on the Gospels.

Ash Wednesday is only two weeks away. It’s common enough – and good enough! – to give up something like alcohol or sweets during Lent. But we might also consider giving up some time. To quote St Josemaría Escrivá, “an hour of study, for a modern apostle, is an hour of prayer.”

It would probably invite failure and discouragement to formulate a Lenten penance which demanded an hour of study every day. But twenty minutes each day can be just as beneficial, and much more feasible.

What to read? Some people read the Catechism. I find it a bit boring personally. An excellent reference, but not engaging reading. Perhaps you might like to read St Thomas himself (although reading the Summa, incomplete though it is, would take longer than a single Lent!). There is no shortage of other (shorter) spiritual classics whose authors have since been canonised. For something more recent, Pope Benedict’s Jesus of Nazareth books are demanding, but they do not presuppose a degree in theology.

In any event, a fortnight is plenty of time to pray and discern a good book to study this Lent.

Good advice as always Father. As you know I love to study Theology but teaching, even CRT, does demand a lot of time so perhaps it would be good if I got back into something solid instead of wasting time on T.V or dare I say it Facebook!

Let’s not even mention blogs! Ha ha.

The Summa itself! Good on you! Which edition? Blackfriars?

Hi Fr Corrigan, I really enjoyed your sermon today, and it’s nice to see here something to remind me of the practical suggestions you gave. I think I’ll follow your advice in trying to fit in 20 minutes of reading the Summa each day…. I have the complete set in English on my shelf, so I may as well get started on it!

Yes, Fr John, it is very important to know and understand our religion. If we do not know and understand, then we remain ignorant and if we remain ignorant, we are not able to love God with our whole being as we not do not know our Creator, Our Saviour and Our Sanctifier. The only way we can learn is in the language that we can understand. If our understanding is removed, then we will not be able to Believe in the God who loves us.

Ur posting, “Why every Christian should be a theologian | Blog of a Country Priest” was worth writing a comment here!

Just wanted to say u did a fantastic job. Many thanks -Gertie