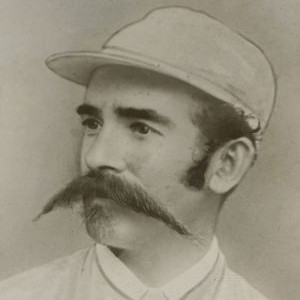

On this day in 1894 the champion jockey Tommy Corrigan died of brain lacerations, two days after he and his horse Waiter fell in the Caulfield Grand National Steeplechase.

He was born in Ireland, but his family migrated to Australia when he was 13. He worked for his father on a dairy farm near Woodford but at age 14, his racing career was launched with a win in Warrnambool. Later on, he settled in Ballarat. I don’t think we’re related — not closely — so it’s pure coincidence that we share surnames and hometowns. (In any event, I’m connected to Ballarat via O’Hehirs and Warrnambool via McElgunns. The Corrigan side of the family comes from outback Queensland.)

Tommy Corrigan was the greatest Australian jockey of the nineteenth century, and some call him the best jumps rider ever. Between 1866 and 1894 he recorded 238 wins, 135 seconds and 95 thirds from 788 starts. That’s a 60 per cent strike rate. I’m a bit surprised that he doesn’t have an entry in Wikipedia. Maybe I’ll do something about that.

The diminutive Irishman’s fame was huge, and like all popular Australian athletes, it was his good nature and beaming smile which shielded him from the tall poppy syndrome. We could imagine him as a 19th century version of Pat Rafter, or even better, another Michelle Payne! By all accounts, he was devoted to his family, and to his Catholic faith. He sought out a priest and made a good confession before every race, and 11 August 1894 was no exception.

For two days, his life hung in the balance, and for two days crowds milled through St Francis’ Church, praying for his recovery. His funeral was the largest ever seen in Melbourne. Traffic was suspended for two hours, and most businesses were closed all day. The route from his home in Caulfield to his grave in Carlton was lined by thousands of mourners, and onlookers described Swanston Street as “a mass of humanity.”

The great jockey is memorialised in a poem by Banjo Paterson:

You talk of riders on the flat, of nerve and pluck and pace—

Not one in fifty has the nerve to ride a steeplechase.

It’s right enough, while horses pull and take their fences strong,

To rush a flier to the front and bring the field along;

But what about the last half-mile, with horses blown and beat—

When every jump means all you know to keep him on his feet.When any slip means sudden death—with wife and child to keep—

It needs some nerve to draw the whip and flog him at the leap—

But Corrigan would ride them out, by danger undismayed,

He never flinched at fence or wall, he never was afraid;

With easy seat and nerve of steel, light hand and smiling face,

He held the rushing horses back, and made the sluggards race.He gave the shirkers extra heart, he steadied down the rash,

He rode great clumsy boring brutes, and chanced a fatal smash;

He got the rushing Wymlet home that never jumped at all—

But clambered over every fence and clouted every wall.

You should have heard the cheers, my boys, that shook the members’ stand

Whenever Tommy Corrigan weighed out to ride Lone Hand.They were, indeed, a glorious pair—the great upstanding horse,

The gamest jockey on his back that ever faced a course.

Though weight was big and pace was hot and fences stiff and tall,

“You follow Tommy Corrigan” was passed to one and all.

And every man on Ballarat raised all he could command

To put on Tommy Corrigan when riding old Lone Hand.But now we’ll keep his memory green while horsemen come and go;

We may not see his like again where silks and satins glow.

We’ll drink to him in silence, boys—he’s followed down the track

Where many a good man went before, but never one came back.

And, let us hope, in that far land where the shades of brave men reign,

The gallant Tommy Corrigan will ride Lone Hand again.

That’s a good yarn. What a legend. Thanks