One of the things psychology has taught me is that the human brain is hardwired for story. It’s how we derive meaning. Story is how we make sense of the world. I think it’s related to something else I’ve learned in psychology: We’re not thinking beings who sometimes feel; we’re emotional beings who sometimes think. And so, for that reason, it’s not enough for us just to learn facts, and to recite facts, like a machine. We need stories to make sense of the facts, and our emotional response.

Here’s a really simple example: imagine you join the whole family for Easter lunch at Grandma’s. Just after you arrive, you greet your cousin Oliver, whom you haven’t seen since Christmas. “Hey Oliver! It’s great to see you!” you say, moving in for a hug. Oliver averts his gaze, sighs deeply, and walks away. Bang! You will immediately go into storytelling mode. Here’s the fact: your cousin snubbed you. But you want more than a fact. You need a story. So you scan your memory. “Did I say something at Christmas, which might have offended him?” “Have I talked about him recently, which got back to him? Maybe you ask around. “Hey, what’s up with Oliver?” You want more facts. But they’re not facts for facts’ sake. They’re facts which can fill in the story you’re telling, to make sense of the world.

We’re doing this all the time. Constantly. The human mind is hardwired for story.

Our salvation history

The Easter liturgy tells a story. It’s the greatest story ever told: the salvation history of the human race. It starts in Eden, before evil entered the world, when God walked the earth.

The story includes Passover, when Moses led God’s People out of Egypt and into the Promised Land. They followed a cloud by day, and a pillar of fire by night. The Presence of God journeyed with them, in the Ark of the Covenant, housed in a tent. Also known as a tabernacle.

Later, King David planned a Temple to house the Divine Presence, and his son, King Solomon built it. The Temple of Solomon was one of the great wonders of the Ancient World, renowned for its luxury and stature. But then the Temple was destroyed, and the Chosen People were exiled. So God raised up prophets, to encourage the people. They foretold the coming of the Messiah, the anointed one, the Christ.

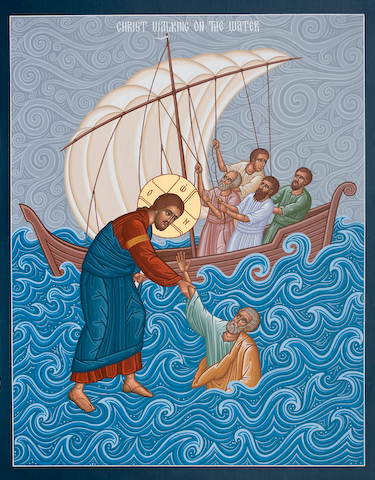

The salvation history of the human race culminates in Jesus Christ. The Messiah. The Son of God. God Himself! For the first time since Eden, God walked the earth. He dwelt among us. But then we killed him. When Jesus died, the veil in the (new) Temple was torn in two. The Divine Presence had left the building. But on the third day, God the Father breathed God the Spirit back into God the Son, and the Divine Presence has never left the earth again. The body and blood of the Son is present in tabernacles throughout the world. And the Holy Trinity dwells in every one of the baptised. Our bodies have become Temples, where the Divine Presence dwells.

Good stories and true stories

This is the story of our faith, and like all good stories, it helps us make sense of the world. When we suffer, we can interpret our experiences in light of the cross, and the resurrection. For example, it’s easy to imagine the actors at the centre of the Australian cricket scandal evoking — at least in a private capacity — some of the motifs of Good Friday and Easter Sunday. It is, after all, the definitive story of loss and redemption. As people of faith we can hope, for their sakes, that they do have a spiritual life, a life of faith, to draw upon. Because it’s true, isn’t it, that in our own darkest moments, we rely on faith? And we wonder how people without faith can live without it.

Our faith provides us with a story which guides our lives. But here’s the thing about stories: they’re not measured only by utility. “Helpful stories” and “unhelpful stories.” They’re also measured by truth. Cousin Oliver can give a good example. Let’s say you’ve asked around, and you’ve done some thinking, and you’ve concluded that Oliver has had it in for you since you were kids. He’s never really grown up. It’s also part of your story that two can play at that game, and you’ll ignore him the way he has ignored you. Or maybe part of your story is that you’re bigger than this; you’ll be gracious to him regardless.

This is how a story is greater than a single fact, “my cousin snubbed me.” Stories help us not only to process the facts, but also respond to them, framing our actions. But what if your story is wrong? It turns out Oliver’s best friend died yesterday, and he only just received the news when you arrived. He was so overwhelmed with shock and grief that he didn’t even see you as he walked past, and his behaviour had nothing to do with you at all. Then it turns out that the story you told, about childhood grudges, however useful it was to interpretation and action, was false. The truth is important. Facts matter.

Passing on the faith

Pope Francis was in the news this week. A journalist friend of his declared that the pope denies the existence of hell. Eugenio Scalfari claimed that when he asked Francis about souls who reject eternity with God in Heaven, the pope replied that such souls cease to exist. They are annihilated. The Catholic world was in an uproar, and the Vatican had to release a statement reminding everyone that this conversation was not recorded, the pope was not directly quoted, and we owe the Holy Father the benefit of the doubt. Why the uproar? Because not even the pope — who is infallible in matters of faith and morals — can change the facts in our story of faith. The facts are passed down to us, from generation to generation, just as we pass the light of Christ from candle to candle in the Easter Vigil. Jesus spoke about hell often, a teaching which was repeated by the apostles, and handed down, generation to generation. Not even the pope can change that teaching.

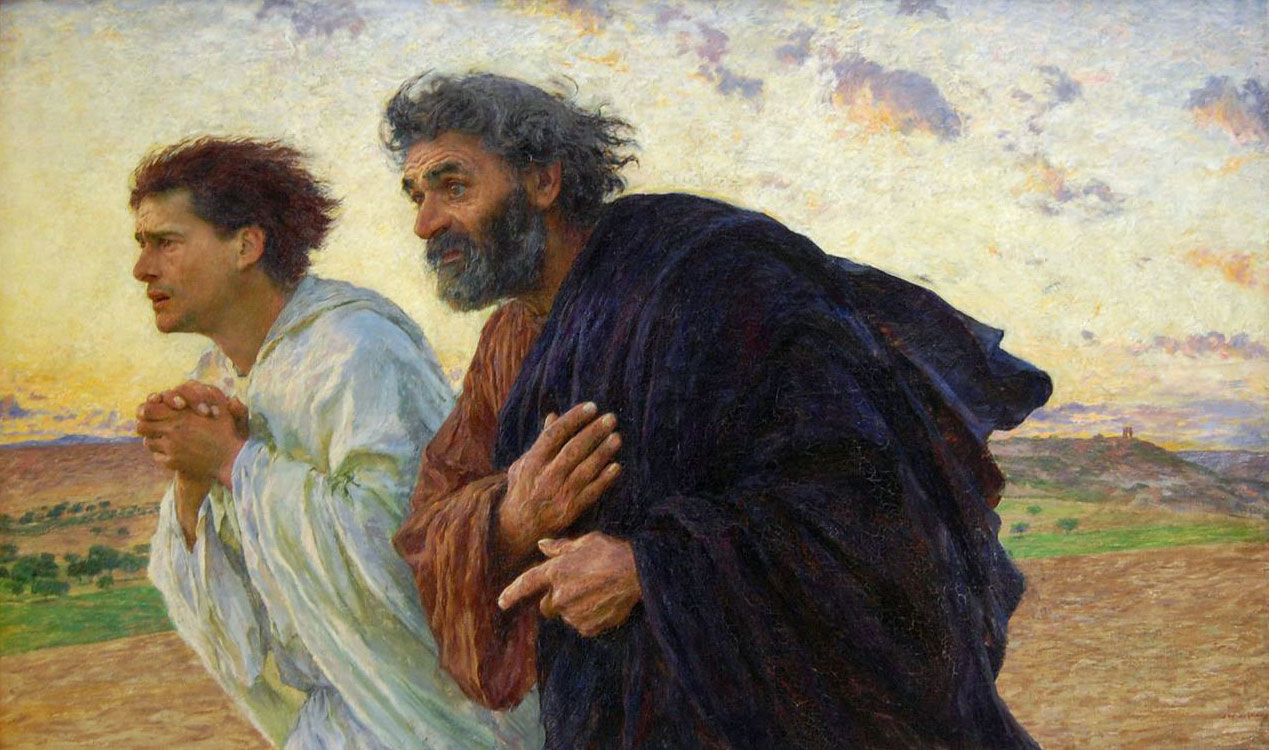

Here’s another one of the facts in our story of faith, perhaps the most important of all: Jesus is risen from the dead. Although our faith is filled with unanswered questions, unanswerable questions, and mystery, everything hinges on this extraordinary claim: The tomb is empty. We have to insist on this. The resurrection of Jesus isn’t something that is “symbolic” or esoterically spiritual. It’s real. It’s spiritual and physical. St Paul declares that if the dead body of Jesus was found, Christianity would pack it in. The Church would close shop. Here are Paul’s exact words, straight from the Bible: “if Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation has been in vain and your faith has been in vain.” (1 Cor 15:14)  The tomb is as empty as an Easter egg is hollow. This is one of the reasons we have Easter eggs — they are a reminder of the startling discovery of Easter Sunday morning. The tomb is empty! Jesus is risen!

The tomb is as empty as an Easter egg is hollow. This is one of the reasons we have Easter eggs — they are a reminder of the startling discovery of Easter Sunday morning. The tomb is empty! Jesus is risen!

Dear Father it is a long time between posts. I always look forward to your posts. I pop in every day to see if there is something new. Then I have to make my own story as to why there are no posts.

I like your new website, so you must fill it with new posts.

Thanks Peter! It’s a new resolution of mine to blog at least three times a week. Hence the “renovations,” to get the blog up to the latest web standards.

Frankly, I’m amazed that anyone bothers to check in anymore. You’ll see much more activity from now on.

Happy Easter!