When a man applies to join the seminary, one of the hoops he jumps through is a psychological assessment. The Church doesn’t want anyone too strange becoming a priest. Which is ironic, because the psychologist I saw was one of the strangest men I’ve ever met.

My appointment was at 2pm, and I rang the doorbell right on the dot, but the psychologist was surprised to see me! He said I was due at 2:30. I later learned that the other seminarians went through the same thing. I think he wanted to know how we’d react to a socially awkward situation.

After I apologised for the “mix up,” I was left in his study while he tidied up in the kitchen. I was left waiting for about ten minutes. Again, I later learned that all the other seminarians went through the same thing. I like to imagine that he had a peephole built into the eyes of an oil painting, so that he could watch what I did while I waited. When he returned, he observed me for a while, and then he said, “You have a young-looking face. Even when you are 60, you’ll look 20 years younger than you are.” What are you supposed to say to something like that??

The psychological assessment took an hour. First there was an ink blot test. Then I was shown photos of people from the 1950s, and asked to indicate if they were ugly, average, or good-looking. Then he read out phrases, and I had to reply with the first thing that came to mind.

Eventually, he declared that I was “boringly normal.” But he did add that I have a volcanic temper. “You don’t lose your temper often,” he said, “but when you do, you blow your stack.” I’d never experienced that before. I didn’t agree with him. But I thanked him, went on my way, and obviously I was accepted into the seminary.

About 2 years later, the psychologist was completely vindicated. Something happened which filled me with white hot rage. I didn’t get violent, but I struggled to sleep at night. I struggled to concentrate during the day. Anger clouded my vision and monopolised my thoughts.

I consulted a priest — as you do. He was excellent. As I told my story, he didn’t interrupt, and he never told me to calm down. I was so angry I swore — which I never did, especially in the company of a priest! But he didn’t flinch.

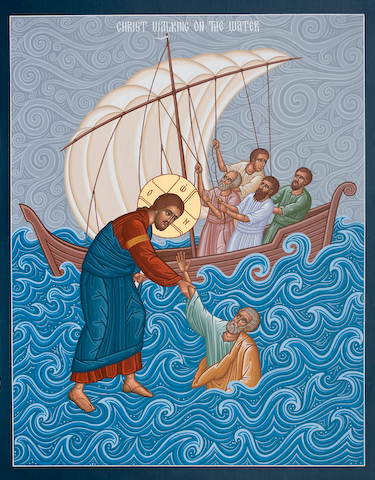

At the end of my spiel, the first thing he spoke of was “righteous anger.” He invoked today’s Gospel. Jesus “is like us in all things but sin.” And yet in the cleansing of the Temple we see him angry. Violently angry. That demonstrates that anger is not, in itself, sinful. It’s easy to forget that. People often confess anger as though it’s a sin. But it’s not always. Righteous anger is a thing. Sometimes, justice compels us to be angry. Certainly, it compelled our Lord.

When I hear or read today’s Gospel, my mind always goes back to that conversation with a good priest in the midst of my anger. What he said next is also important. Having identified the righteousness of my anger, he also identified wrath: one of the seven deadly sins. And with that, he donned a purple stole, and declared it was time for confession.

I had to pause a moment and examine my conscience. What is the difference between righteous anger, which even Jesus exercised, and wrath, which is a deadly sin? With the Holy Spirit’s help, I discerned the answer, because when we approach the Sacrament of Reconciliation in good faith, the Holy Spirit will always assist us. (Guaranteed!)

Righteous anger is godly; it derives from justice. Wrath is ungodly; it excludes mercy. And there is the crux. In God, we find infinite Justice and infinite Mercy. There’s tension between them, but they’re not opposed. On the contrary: in God, justice and mercy are perfectly united; two sides to the one coin. But in our human frailty, justice and mercy can be opposed. And wrath is just one example of what that opposition looks like.

There’s a reason wrath is called a deadly sin. Its fruits are toxic. In my case, it caused inestimable damage to several relationships. Years later, those relationships are salvaged, but scarred. Nonetheless, despite its lasting damage, I don’t regret that terrible experience. Which brings me to today’s Second Reading — one of my favourites. In his first letter to the Corinthians, St Paul describes Christ crucified as “an obstacle” to the Jewish mind and “madness” to the pagan mind. But to the Christian mind, the crucifixion is “the power and the wisdom of God.”

In his second letter to the same, St Paul elaborates on what he wrote in his first letter: God’s power is made perfect in our weakness; when we are weak, then God is strong.

The wrath which afflicted me — the deadly sin which I committed — diminished me. It hurt people I love, and it cut me off from God’s friendship. But in confession, I was reconciled with God. And the grace that flowed from that helped me to repudiate the spirit of wrath, forgive my friends, and enable them to forgive me. That healing, unlike the absolution it flowed from, wasn’t instantaneous. It happened slowly, painfully, but inexorably.

Many years later, there are still scars, because grave sins always leave scars. They aren’t healed in this life — some things have to wait for the next. But in the meantime these scars we all carry are assets. Paul even suggests we boast of them, because in these God’s power is made perfect.

In my case, that terrible, unforgettable experience gives me insight into other people’s struggles with wrath and unforgiveness. And I have insight into righteous anger too, and how to discern that from wrath. All of which helps me to counsel others as I was once counselled. But most importantly, it keeps me humble. I know that I have to struggle to be like the Lord: slow to anger, rich in mercy.

This is just one example of how weakness — even sinfulness — can strengthen us. Not automatically! It’s never automatic. We have to pray through our weakness. We have to approach Christ, on his cross, and suffer with him. But when we do that, our wounds become fountains of grace. In and through the cross, we’re able to bless the people around us. And we can say with St Paul, “when I am weak, then I am strong.”

Thankyou Father

Anger = wrath. Both can be righteous. That is why there is such a thing as the Wrath of God. Anger or wrath is healthy and good when it is directed at, and only at, EVIL. There is such as thing as objective anger, one that compels you to punish evildoers. Without it, evil will flourish. Then there is such a thing as sentimental anger, one that comes from being spurned by a loved one, or betrayed by a trusted person. This is no longer righteous anger, but vengeful selfish anger. Vengeful anger is one that you’d be better off leaving to God. “Vengeance is Mine” says God. But for the other kind of anger, you need it to inflict punishment against rapists, murderers. swindlers, etc.

I don’t know Alex. I agree, but I disagree. Now we get to the limitations of language.

For example, after Mass this morning, a parishioner approached me and explained that when he was a child — a half century before I was born — the cleansing of the Temple was explained as “just indignation.” He recognised “righteous anger” as its equivalent. I didn’t say it to him, but I’ll say it here: I can’t see how “indignation” could possibly describe the fury which caused our Lord to wield a whip and overturn tables. I like “righteous anger” much more.

Traditionally, it is true, we can speak of “the wrath of God.” But of course it is also ancient and pious tradition to refer to one of the deadly sins as wrath. Hence my reluctance to apply wrath to God, just as I hesitate to describe the cleansing of the Temple as “indignation.” Semantics, really, but still . . .

I like that you’ve introduced vengeance to the conversation. Isn’t it interesting that vengeance is a deadly sin distinct from wrath? Certainly in my experience, there was nothing vengeful about the wrath which afflicted me. Vengeance is something quite distinct from anger — hence the saying, “don’t get mad; get even.” And yet, as you observe, “Vengeance is mine, says the Lord.” So scripture applies vengeance to God, just as it applies wrath — even while Tradition describes both as deadly sins. The limitations of language!

But then you raise another point entirely. Punishment. Or better: retributive justice. I don’t think that should relate to anger at all. Even righteous anger. Retributive justice, I think, needs to be totally rational, to the exclusion of anything relating to the passions. Toby Zeigler kind of elaborates:

(On a related note, never let anyone persuade you that Game of Thrones or The Sopranos or Dexter or whatever is TV’s best series ever. No way. That title is OWNED by The West Wing — with an honourable mention going to Brideshead Revisited, which being only one season is strictly a thirteen part “mini-series.”)

thank you for your honesty you have made clear something I have often pondered over.

Once again Father, I’m sorry for putting the tomatoe sauce back in the fridge. I was just following the instructions on the label.

Seriously, good post mate. Yeah, that shrink was a nut. You failed to mention the toupee that looked like a dead bandicoot.

Fantastic blog. My bro recently described me to a group of friends as possessing the rare quality of “righteous anger”. At that point I immediately hoped people didn’t misunderstand and think I am an angry person, which I am not :-), I think they got his meaning though since they all knew me well.

In your blog you said something interesting: “Justice compels us to be angry” as it compelled our Lord. But Justice also compelled Jesus to to be more than angry, it compelled him to act. So here is my question. If we feel righteously angry at something but fail to act, is that sinful?

Hello I back with racing tips! Before that Neigbours the show is Celebrating 30 years on Monday night special inside of the show on channel Ten on 7.30 pm!

We all know we have that show on this blog!

Racing tomorrow at Flemington 2 Big Races!

Race2No3 and 7 Race3No9 Race5No13 Race6No4 and 7 Race7No1,4,15 Race8no6and 11 Race9 No4,8 and 10.

Race six is the Newmarket Handicap is Group One Race for the sprinters now the straight if you been to Flemington! Race7 is the Australian Cup! It’s another group one! Red Cadedaux is back from England it has ran in 4 Melbourne Cups with three thirds ! Tomorrow distance might be too short of it 2000 metres!

Now Sydney Race2No13 Race 6 No4 Race7 No1 and 6 Race8 No10 and Race9 No5 and 11.

Remember Each way and there some jumps racing at Oakbank on Sunday! Keep Well from Simon the Pieman.

I know two people love my tips that is Fr. Madden and the young sportsman deacon Joel Peart! Maybe they should give us some tips of some history! Have a good weekend and Happy Punting!